The right to stay real

Arul George Scaria on protecting autonomy and dignity in the age of AI

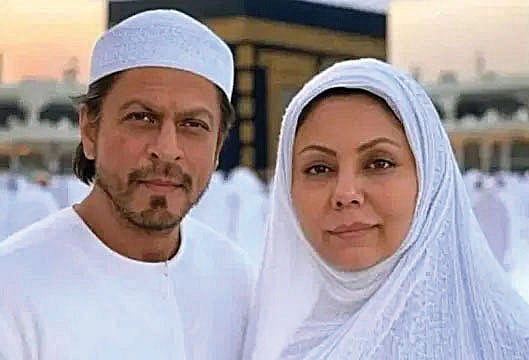

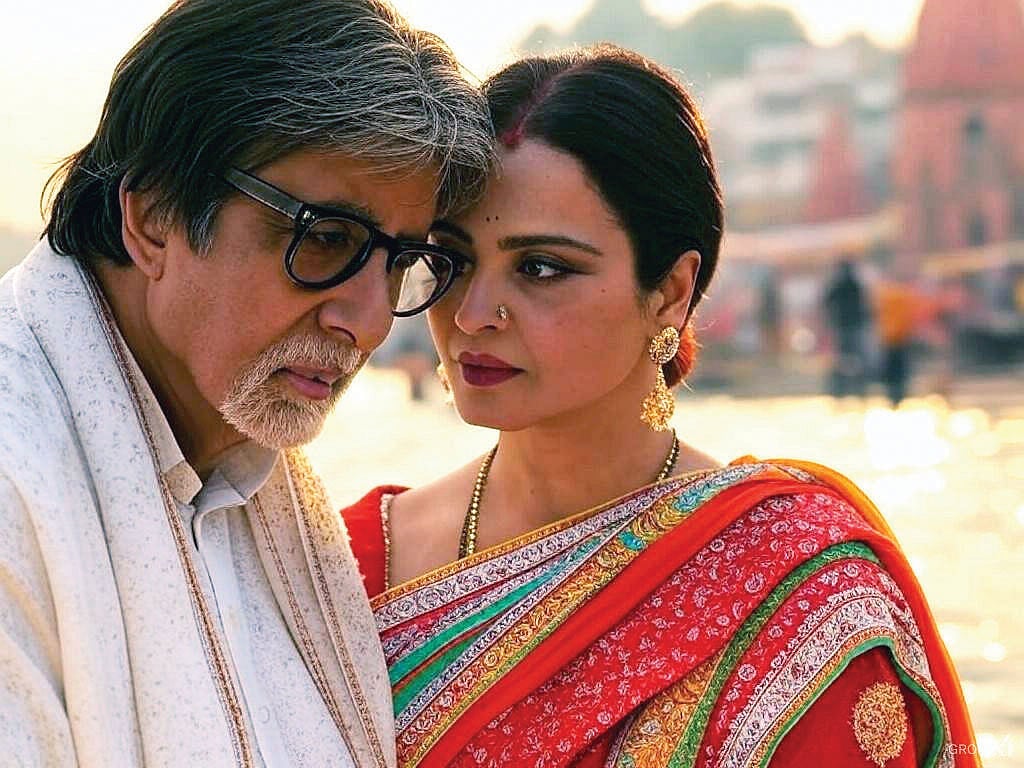

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly changing, challenging and reshaping the manner in which creative artefacts are generated and used. This has led to a multitude of complex legal and ethical issues. A series of recent cases involving celebrities like Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, Asha Bhosle, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar and others has brought into focus one of many such issues — the unauthorised use of an individual’s face, voice, likeness and other attributes in the emerging AI context.

Indians are well acquainted with the unauthorised use of image/ voice/ likeness of celebrities. Travelling through India, we’ve all seen billboards plastered with advertisements featuring celebs, a substantial chunk of these quite visibly fake. Even the better produced ones are not necessarily authentic endorsements by the featured celebrities. A line of dialogue, a scene from a movie and sundry other unauthorised copy-paste fragments may be used to create an indirect association between the brand and the celebrity.

While most celebrities would disapprove of such unauthorised associations, they may have acquiesced in the past, either because the economic fallout was not substantial and/or the sense of personal violation not so great.

Likewise, many local performers are known to imitate voices of famous singers in their own live shows. While most big-name singers are aware of the practice, they have generally not bothered to make official complaints, for similar reasons and perhaps also because imitation too extends their fame.

In the AI context, what takes this kind of unauthorised use into a threatening realm is the sheer scale of ‘generative’ possibilities and the increasing sophistication of fake reproductions, making it nearly impossible for most to distinguish between the original and the AI- generated fake.

Also Read: A question of integrity in the time of AI

The widespread availability of AI tools, particularly Generative AI tools, has meant that even people with minimal tech or creative expertise are able to generate high-fidelity images, audio clips and videos, using just a few prompts.

For celebrities, the consequences of such misuse can now extend far beyond financial loss. For instance, when an AI-generated video depicts a celebrity endorsing a particular herbal remedy, there is a very high probability that the public will perceive it as genuine advice and follow it blindly without verification.

It doesn’t take much to imagine how these GenAI impersonations can take far more dangerous turns, going way beyond encroachments on privacy, autonomy or individual dignity.

The legal tangle

India does not have a sui generis law for protecting publicity rights or personality rights, but courts in India have been using constitutional law principles, a mix of different statutory provisions and common law principles to provide remedies in most instances.

While the courts have generally ruled in favour of the celebrities seeking protection against unauthorised exploitation of their persona, it is important to recognise the inherent limitations of judicial mechanisms to address the whole panoply of related issues.

This includes the impracticality of approaching the courts to address every violation, especially when tools enabling such violations are widely available to the public without any restrictions. Although the courts have, in some instances, allowed complainants to move to the administrative side of the judiciary to add more defendants, this approach has practical limitations.

There are uncertainties even about the limits of protection. For example, while most cases that have come up so far involved potential damage to the goodwill or reputation of complainants and consequently, economic losses, it is important to understand that some uses of deepfake technology may be legitimate — for example, parody and satire.

It is only through extensive deliberations and consultations that we can identify the scope of potential rights and their limitations. More deliberation is needed on fundamental questions like should protection (of their persona) cease upon the death of a person. The answers to these questions will depend on the theoretical framework and policy rationale we adopt to grant protection.

Most importantly, we need to think beyond celebrities, since the issues affect every one of us. Would anyone like to see their or their children’s photographs becoming fodder for GenAI content, without their consent?

These are not hypothetical scenarios: many AI platforms prompt users to upload their photographs to generate images in different styles. When these photographs and AI-generated output are used for subsequent training of AI models, producing output that resembles the original, it becomes critical to ensure the availability of effective remedies.

While the recently released draft amendments to Intermediary Guidelines aim to address some of the labelling concerns, what is really needed is a comprehensive governance framework for AI-generated content, along with robust data-protection measures.

Practically feasible disclosure requirements with respect to AI training, informed consent, mandatory labelling of synthetic output and opt-out provisions are a must in the current context. Also, strong and independent redress mechanisms.

Without a robust legal and regulatory framework, we risk losing control. Not only over images and voices, but autonomy and dignity.

Arul George Scaria is a professor of law at NLSIU, Bengaluru

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines