Nation

The first polls after delimitation

This is significant because in the last election, the BJP-led coalition bagged 75 seats while the Congress-led coalition won 50

The assembly election in Assam this time will be the first after the controversial delimitation of constituencies in 2023. (The last election was five years ago, with polling held in three phases.) Delimitation affected around 40 constituencies out of 126, and led to considerable confusion.

While the number of constituencies is the same, the names of several have changed, boundaries have been redrawn and, in some cases, two independent constituencies have been merged (for instance, Hajo Sualkuchi, Bhabanipur-Sorbagh).

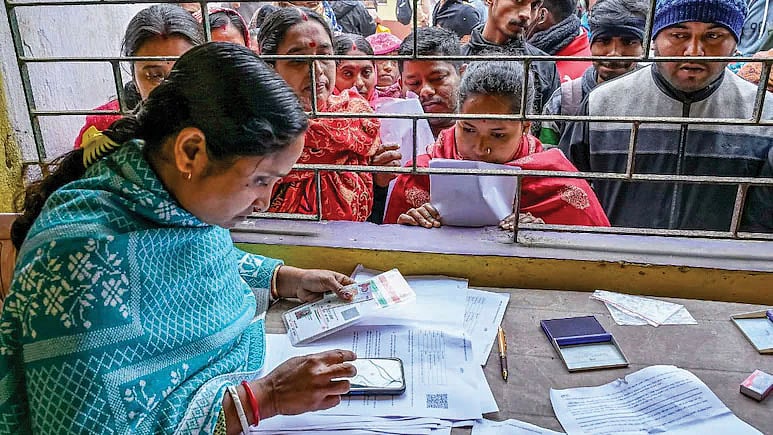

As a result, many voters in Guwahati are uncertain of their constituency. The confusion extends to political parties as well. Party workers are busy scrutinising the final electoral roll issued by the election commission on 10 February 2026 after the Special Revision (SR) of electoral rolls. Political parties have an additional task—finding the right candidates in view of the changed character and demography of the constituencies. In 2022, Jammu and Kashmir underwent a similar delimitation exercise and six new constituencies were added.

In Assam, the number of assembly seats was frozen. However, the Assam cabinet pre-emptively folded four districts back into the districts from which they had been separated, reducing the number of districts from 35 to 31. The merger led to the loss of several Muslim-majority constituencies—South Salmara, Barpeta (two seats), Darrang, Nagaon, Sibsagar, Hailakandi and Karimganj—while the number of seats dominated by Hindus and tribals increased.

As in J&K, the Assam delimitation also created constituencies of vastly different population sizes nestling against each other. The respective delimitation commissions have not hesitated to create small population constituencies alongside large population ones to further marginalise the minorities.

Published: undefined

Before the delimitation, Muslim voters called the shots in 30 of the 126 constituencies in Assam, and substantially influenced the outcome in 10 more. The number of such constituencies is estimated to have gone down by half. (Paradoxically, chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma says Hindus will be reduced to a minority in Assam in the next 10-15 years.) Muslims constituted 34 per cent of the population in the 2011 census and there are 31 Muslim MLAs in the outgoing House. The attempt is to reduce their number and representation to one-sixth of the assembly’s strength.

This is significant because in the last election, the BJP-led coalition bagged 75 seats while the Congress-led coalition won 50. In a closely contested election, every seat counts. By all accounts, the BJP has used both the delimitation and the SR to its advantage.

Both coalitions, however, appear wobbly in the run-up to the election being notified. Despite the ultimatum of the regional party Raijor Dal to finalise seat-sharing by the end of January, negotiations with the Congress spilled into February. Negotiations between the Congress and Lurinjyoti Gogoi’s Asom Jatiyo Parisod are also ongoing. The Communist Party of India, meanwhile, has gone ahead and declared the names of seven candidates, signalling a lack of unity and dissonance.

Luckily for the Opposition, the ruling NDA has its own set of problems. Besides the growing infighting within the BJP and anti-Himanta forces sharpening their knives, allies Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) and the Bodoland People’s Front (BPF) are demanding more seats.

There is little love lost between BPF and the United People’s Party Liberal (UPPL)—the other Bodo indigenous party led by Pramod Boro—making seat distribution more complicated. The BJP, on its part, is pushing the AGP to contest from Muslim majority constituencies in Lower Assam.

Published: undefined

Against this polarised backdrop, Assam BJP’s official X handle circulated an animation in which the chief minister was depicted as a cowboy shooting point-blank at two men in skullcaps. ‘Foreigner-free Assam’ and ‘No mercy’ screamed the text overlays. The outrage that followed forced the party to delete the animation.

Having gotten away with hate speech so far, he clearly did not expect over 40 prominent members of civil society—led by intellectuals including author Hiren Gohain, former DGP Harekrishna Deka, former archbishop Thomas Menamparampil, Rajya Sabha member Ajit Kumar Bhuyan and editor-in-chief of Northeast Now Paresh Malakar—to complain to the chief justice of the Gauhati High Court, seeking judicial intervention and action against him.

For several years now, Himanta has been targeting ‘Miya Muslims’, blaming them for everything.

Has he gone too far this time around? Has the attack on minorities started yielding diminishing returns?

Himanta’s attempts to describe MP and state Congress president Gaurav Gogoi as a ‘Pakistani agent’ does not seem to have had the desired impact. The dramatic two-hour long press conference and release of the report by a SIT set up by the Assam Police highlighted two points: Gogoi’s British wife had worked for a Pakistani NGO for a year; and Gogoi had visited Pakistan in 2013 (notably when he was not an MP). Repeated over the last one year, the allegations have lost much of their sting. Gogoi has justifiably raised the question: if he was truly a threat to national security, why had the SIT not interrogated him even once?

Raijor Dal chief Akhil Gogoi had the last word: “The chief minister has got people arrested for Facebook posts and for writing poems; but here he is unable to arrest a leader he accuses of being a security risk!”

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined