Opinion

Questions a fair-minded ECI cannot ignore

ECI’s stance has been that of a defensive counter-attacker — pointing fingers at those raising doubts instead of dispelling doubts

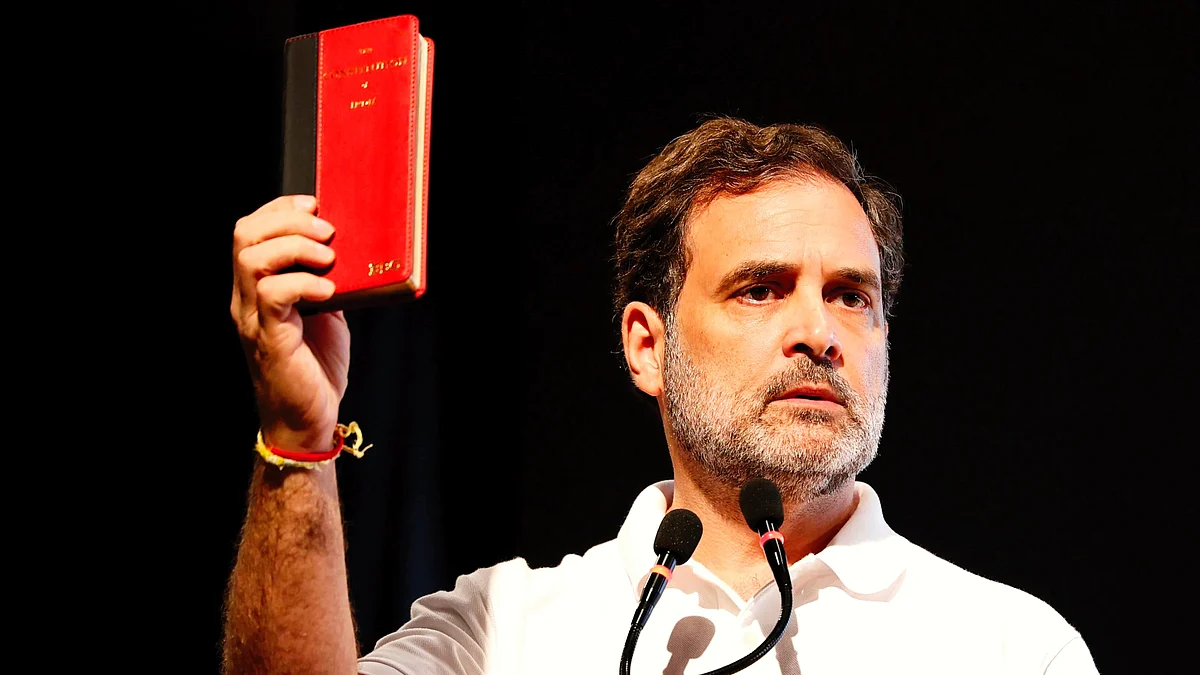

Leader of the Opposition Rahul Gandhi has once again raised serious questions about the credibility of India’s electoral process. Several non-partisan civil society groups and individuals concerned with democratic processes have again echoed his concerns.

Predictably, BJP leaders have hit back. The ball is in the Election Commission’s court. But instead of addressing the issue transparently, the Election Commission of India (ECI) is yet again going through the motions of obfuscation and denial — a most worrying sign for Indian democracy.

The question of electoral credibility is both sensitive and crucial. Every stakeholder must tread carefully. It is easy to blame the process after losing an election — that’s the oldest trick in the book.

So, mere suspicion or a stray irregularity won’t cut it. Anyone alleging electoral fraud must present hard evidence. Conversely, simply claiming that elections were ‘free and fair’ is not enough to validate the process. Elections must not only be fair, they must appear to be fair — and the Election Commission must clear every test of transparency and impartiality.

It’s not that Rahul Gandhi’s recent article made new revelations. He reiterates the same questions he’d raised earlier at a press conference — this time with a sharper focus on Maharashtra. The big question is the mysterious net addition of 4 million voters (4.8 million new names added, 800,000 deleted) in Maharashtra in the six months between the assembly elections and the Lok Sabha polls.

Rahul asks: if in the five full years between 2019 and 2024, the voter base only grew by 3.2 million, how could it suddenly swell by 4 million in just six months? He cites official data to show that such a jump is unprecedented. Even more puzzling, he points out, is that the total number of voters in Maharashtra exceeded the state’s estimated adult population!

Published: undefined

He raises another key question: how did the voter turnout jump from 58 per cent (as declared at 5.00 pm on polling day) to 66 per cent the next day? According to him, this overnight jump occurred mainly in the 12,000 polling booths where the BJP had lost in the Lok Sabha — and could flip the outcome in its favour in the 2024 assembly election by ‘fixing’ these booths.

Rahul Gandhi’s evidence isn’t definitive or watertight, but it is strong enough to raise serious doubts. Back in December 2024, the Election Commission had responded to some of these issues in a letter to the Congress party. The trouble is, the Commission’s stance throughout has been that of a defensive counter-attacker — pointing fingers at those raising doubts instead of dispelling the doubts themselves. Instead of answering the questions, the Commission hides behind legal technicalities.

Take the issue of the bloated voter rolls. The ECI says: our voter list revision process is flawless, and all parties were given a chance to object at every stage — you didn’t raise objections back then. Let’s assume that’s true, and that the opposition parties did drop the ball during the revision process. Even so, isn’t it the Commission’s duty to examine the lists proactively? If the paperwork is so perfect, how did we end up with 5.6 million changes in six months? Who are these 4.8 million new voters? Why were 800,000 names struck off?

Maybe there’s a legitimate explanation — but when questions are posed to the Election Commission and replies come from BJP spokespersons, the suspicion only deepens.

The core issue is this: if Rahul Gandhi or anyone else wants to prove electoral fraud, how are they supposed to do it? The Commission keeps withholding critical information from the public. Whatever the validity of Rahul’s other points, his fundamental question is rock solid: why doesn’t the Election Commission make the data public?

Published: undefined

To verify whether voter rolls were tampered with, you need soft copies of booth-level rolls for both the assembly and Lok Sabha elections — so you can compare them. The Commission has uploaded the latest list online but has deleted the older one. If you had to prove that the number of votes cast after 5 p.m. at a particular booth were lower than what the ECI claims, you’ll need CCTV footage, which the poll panel has refused to release. Worse, the government has quietly changed the rules that allowed citizens to even request such information.

Since the Lok Sabha elections, several parties and civil society groups have been demanding that Form 17C, which records the number of votes polled at each booth, be made public. The Election Commission keeps dodging the demand with one excuse or another, lending substance to the public perception that something fishy is going on.

Two decades ago, if a losing party had raised such questions (as Mamata Banerjee once did), no one would have taken it seriously. Back then, the Election

Commission had a solid reputation and real clout. Ruling parties were scared of it during elections. But over the past ten years, the ECI has squandered away that credibility. Today, election commissioners act less like heads of an independent constitutional body and more like government officials. Every major election-related decision seems to reflect an understanding between the Election Commission and the BJP.

The Supreme Court tried to fix this by mandating a fairer process for appointing election commissioners. The Modi government quickly undercut that reform by removing the Chief Justice of India from the selection panel and installing the home minister instead. No wonder then, the Election Commission today looks less like an umpire and more like a player in the match.

Among other questions, Rahul Gandhi points an accusing finger at this fundamental flaw in the process of naming our election commissioners, a question every mindful Indian citizen who wishes our democracy well will also ask.

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined