World

Making sense of China’s massive military purge

Most China watchers see Xi’s PLA purges as more profound than Mao's purges after the 1970 Plenum

The most striking outcome of the Chinese Communist Party’s Fourth Plenum in October was the sweeping purge of military officials at every level of the party’s decision-making structure. China specialists, including Francesco Sisci, have called it unparalleled in scale and duration, the biggest faced by the People’s Liberation Army in its hundred-year history.

Eleven alternate members were promoted as full members to the Central Committee—not one was from the PLA. With no new military officers admitted to the party’s top decision-making body, Sisci argues the PLA has, in effect, been “demoted” and “seems to be under suspicion.”

The Plenum was supposed to include 205 full members and 171 alternate members. Notably, 23 full members were absent, and 27 of the 44 military members had already been purged over the past year. Eight of the nine expelled PLA officers were full members of the Central Committee.

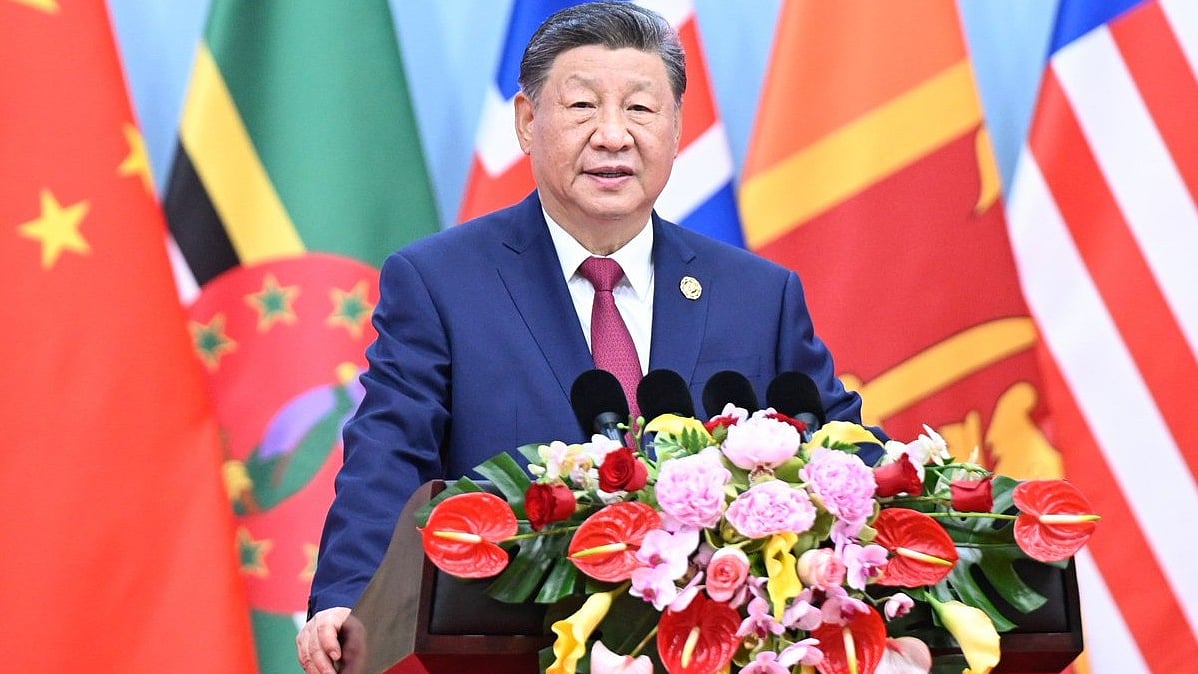

There’s no doubt the sweeping purge was ordered by President Xi Jinping. Though framed as a massive anti-corruption drive to cleanse the Party of nepotism, bribery and embezzlement, it is being seen as a sign of Xi’s deep distrust of the current military leadership.

Historically, military purges often follow failed military coups, as leaders target officers deemed disloyal. Erdoğan’s sweeping crackdown after Turkey’s 2016 coup attempt is a case in point. Hence the question: is Xi’s purge of the PLA a response to a foiled attempt to oust him, or a reflection of his deep-seated suspicion of military personalities who may wish to back a less assertive party boss?

Several sidelined CCP leaders—including Hu Jintao, Wen Jiabao and Hu Chunhua—are reportedly at odds with Xi Jinping and have the support of PLA leaders. The purge of nine senior military officers, including Politburo member General He Weidong, PLA political commissar Admiral Miao Hua and Defence Minister Li Shangfu, opened up three vacancies on the powerful Central Military Commission (CMC). Shangfu was removed last June, following the removal of his predecessor, Wei Fenghe. The Plenum nominated staunch Xi loyalist (in-charge of the anti-corruption drive) 67-year-old Zhang Shengmin as vice chairman of the CMC.

Xi's shrinking military support

The purge of officers who served with Xi in Fujian and Zhejiang provinces two decades ago suggests his support base in the military is shrinking. This has strengthened the influence of 75-year-old Zhang Youxia, senior vice chairman of the CMC, a key figure at this Plenum. Youxia and Shengmin may now be Xi’s most trusted assets against his detractors. Xi’s third big asset is the new PLA vice chairman, Zhang Weisheng, the chief architect of the purges, who investigated and charged the deposed leaders. Like Xi, Weisheng served in the Second Artillery and is from Shaanxi province.

Published: undefined

Most China watchers see Xi’s PLA purges as more profound than Mao's purges after the 1970 Plenum, in the wake of a failed coup attempt by one-time lieutenant and chosen successor Lin Biao, who died in a plane crash in September 1971 while trying to flee the country. Hundreds of PLA officers are under investigation, which might impact the army’s control, command and efficiency—echoing Stalin’s 1930s purges of the Red Army, which left it ill-prepared for the German invasion of 1941.

The Taiwan factor

Xi’s fraying ties with the military may stem from serious differences over Taiwan. Military hardliners have long advocated invasion to settle the issue of reunification. Xi prefers a subtler strategy, which seems to have worked in Hong Kong. This includes intimidation and infiltration of China loyalists in Taiwan’s political structure

Xi has good reason to not risk a spiralling conflict through the military invasion of Taiwan—not least for the forceful pushback it might trigger from the US, the West and possibly Asia. If it succeeds, the generals would claim the credit; if it fails, Xi would be blamed for greenlighting it.

A report by the US-based thinktank Stimson dismissed the likelihood of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, while President Donald Trump claimed Xi Jinping personally ruled it out in a one-on-one meeting. While Trump declarations are best taken with a pinch of salt, Xi and his inner circle have surely drawn lessons from Putin’s protracted invasion of Ukraine.

While the purges may leave the military less than ready for war and constrain Xi Jinping from undertaking a military invasion, his reliance on hybrid tactics—psychological pressure, embedding loyalists and influencing Taiwan’s elections—seems to have brought him into conflict with the generals.

Whatever the cause, Xi is clearly holding fast to Mao’s dictum: the party must command the gun, not the other way round.

SUBIR BHAUMIK is a former correspondent with the BBC and Reuters. He is active on the Kolkata-Kunming Forum, a Track 2 initiative with China

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined