Opinion

The limits of billionaire power

As proven in New York’s recent mayoral elections, people sometimes matter more than money

The first amendment of the United States Constitution reads as follows:

‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances’.

The language seems slightly archaic because it was written in 1789, but is clear enough for us to understand that freedom of speech cannot be curtailed. It can, however, be restricted, for example when related to threats of violence or pornography.

In 2010, the US Supreme Court eliminated restrictions on election funding, ruling that such limits violated the right to free speech under the First Amendment. Corporations and wealthy individuals were now free to influence elections by creating political action committees (PACs) that would spend money on advertising.

This was the outcome of the famous Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (FEC) case which fatally damaged US democracy because both their major political parties are now permanently influenced by corporate interests.

If the reason you won your seat is your donors, then it is likely that your actions in office will also be influenced by them. This seems to have become inescapable in US politics. However, there is another way of doing politics, and though its formula is simple, its execution is very hard.

To attempt something with a high rate of failure takes a certain kind of determination and outlook. To succeed in such a task is truly remarkable. An example of this comes to us from the recent New York mayoral election.

Published: undefined

The two major candidates had two different approaches to contesting. The first approach is the one preferred by both major political parties and their candidates, which is to win by raising more money than the opponent. This money is then deployed chiefly in messaging: television advertising and mailers designed to overwhelm the voter with positive impressions about the candidate paying for the ad and negative ones about the opponent.

The more ads one can put out, the greater the chance of success. A report from 2018 headlined ‘How money affects elections’ found that more than 90 per cent of the time, the candidate who raised and spent more than their rival won their race for a seat in Congress (their version of the Lok Sabha).

Andrew Cuomo, one of the two main candidates in New York, took this approach and raised more than five times the money his opponent had. He lost. Why? (Think about it.)

The second approach is to convince voters not through advertising but personal conversations. This is effective but does not seem to be scalable. It seems especially absurd to attempt it in a general election where voters number in the millions.

The number of people required on such a staggering scale would surely cost more than advertising. And it would be difficult for these people to open conversations with strangers, because many at home would either not answer the door or, having answered it, would promptly ask the person to leave or, if accosted in the street, would simply not stop.

Even if they chose to speak, it would not be easy to convince them to vote for the candidate. After all these ifs and buts, the success rate is likely worse than 1 in 10. Meaning that for every person that is convinced into voting for the candidate, another 10 slam the door, say they will support the other side, or just walk on.

Published: undefined

How would one keep these workers motivated? What would prevent them from pretending they had been knocking on doors and stopping strangers on the street, when they’d actually stayed at home or whiled away time in a café? These are some of the reasons this second approach is not preferred and why candidates choose to just raise more money.

It can only succeed under certain conditions.

First, that the message is compelling to a large number of potential voters. Second, that workers are highly motivated and not put off by the high rate of failure. The motivation here is not money but the cause. It is similar to propagation and proselytising. Third, that there is some mechanism that monitors the engagement and sees it through to voting day. Meaning to repeatedly stay in touch with people once contact is made.

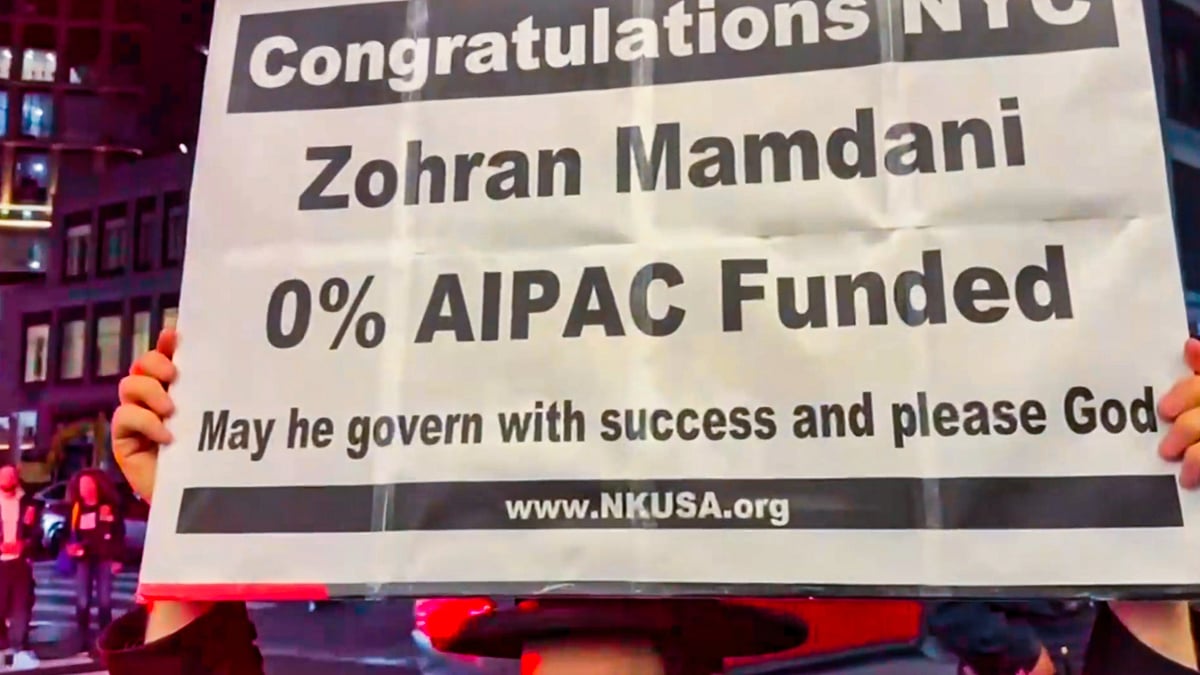

This was the approach used by Zohran Mamdani, the Indian-origin socialist who won the election on 4 November and will be New York’s next mayor. Those who say he is inexperienced and knows little about leadership do not understand he has already displayed the highest level of leadership: by motivating people to throw themselves into something known to have a high rate of failure, and then succeed at it.

An army of over 1 lakh volunteers trained and led by 700 senior volunteers worked for Mamdani’s campaign. While most were young, there were also many middle-aged and old people who willingly gave hours, doing physical work over many months for the cause they believed in.

More than $40 million was spent by corporates backing Andrew Cuomo to paint Mamdani as a terrorist. They lost to the volunteers who were paid nothing.

This win will be studied for a long time because it reduces to bare essence the two approaches to winning elections and shows the limits of billionaire power. As activists in America say: They have money, we have people.

Views are personal. More of Aakar Patel’s writing may be read here

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined