RESET: The post office effect

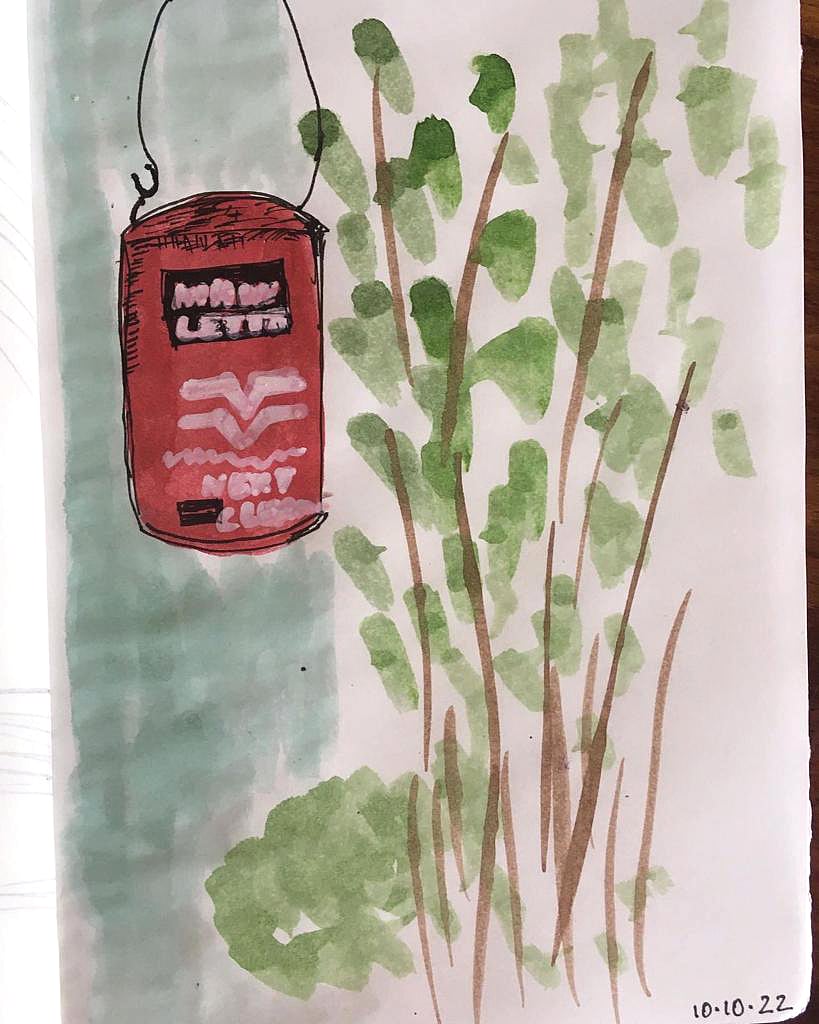

Lalita Iyer on her ongoing affair with handwritten letters and the reassuring sight of the obsolescent red postbox

I am a letter writer in an age where people consider a social media ‘like’ a conversation. I also always choose India Post over couriers. The reason? I just love how a post office makes me feel—that sense of time standing still in some spaces, no matter how much the world changes around us.

Growing up, we were surrounded by red letter boxes. There were at least three in the walk from my home to school. In bigger, busier areas, there were also blue ones (for metros) and green ones (to indicate local post).

As a child, I often stood in front of these boxes and spent several minutes deliberating over which box my letters, New Year or Diwali cards should go into and wondering what would happen if a letter went into the wrong box? I also wondered if there was a place that missing letters ended up in and fantasised about a Museum of Lost Letters. Oh, the possibilities!

‘The proper definition of a man is an animal that writes letters,’ wrote Lewis Carroll. While the excitement attached to the receipt of a reply was unparalleled, it feels good even now to remember little me visualising the journey of my letter once I had dropped it into the post box. Where would it be at this point? Which river or ocean would it be crossing? When would it reach my friend? Would she be home when it arrived? Would she read it once or many times? Would she keep it carefully? Would she write back immediately? What paper would she use?

That child-like joy at envisioning every stage of the letter’s journey seems to have found its adult counterpart in my enjoyment of the process of tracking, thanks to Speed Post services (a definite upgrade for all things travelling by post).

It’s fascinating to see how a parcel coming to me from Gurgaon or Guwahati travels so many thousands of kilometres, across so many states, so many landscapes, in so many modes of transport before finally being brought to my doorstep by a postman (or woman) on a bicycle or scooty.

My affair with the post office was in hibernation for almost two decades of my life, until it was rekindled, strangely enough, during the pandemic. I wanted to send gratitude packages—books, embroidered fabric, odds and ends, always with a letter, to thank those who sent me care packages when I was holed up in bed with a fracture during the first lockdown.

My son’s pandemic birthday was a ‘letter party’ where friends, both virtual and real, sent him loving letters and cards which we read together. It felt like the whole world had showed up for us through their words. India Post was classified as ‘essential services’ and I was grateful.

With over 1.55 lakh post offices, most of them in rural areas, India has the largest postal network in the world. The network has grown seven-fold since Independence, mostly in rural areas. Yet, the growth in terms of numbers and reach is slowing down and post offices are scrambling to stay relevant and profitable.

When I moved from Saligao to another village in Goa, I was in no-man’s land as far as the post office was concerned. My official address, per the electricity department was Alto-Porvorim but for months the post office refused to deliver mail, stating that the area fell under the jurisdiction of the Salvador do Mundo Panchayat.

While most of the Amazon/Zomato populace were unaffected, it bothered a few of us to not be able to receive post at home. Friends from all over were eager to send me parcels and, for someone who had a steady bond with the post office for the past few years, it felt like something was amiss.

After several letters to the sarpanch and other powers that be, the postman showed up at our gate, and almost received a red-carpet welcome from the ones among us who cared enough for this vestige of our past.

I’ve noticed that senior citizens feel at home in the post office—there are always many of them there. Perhaps it’s the only place in the world where they don’t need an app to check their balance, don’t have to speak to a robot on the phone, or wait for an OTP to accept a parcel or update an address.

Post office savings schemes are hugely popular in both urban and rural India and it is reassuring to see so many people waiting to get their passbooks updated, server speed notwithstanding.

And as post offices also provide life insurance cover under Postal Life Insurance (PLI) and Rural Postal Life Insurance (RPLI) as well as retail services like bill collection, sale of forms, etc., it’s really a one-stop shop for the ‘oldies’.

Unlike banks and financial institutions, the post office is still low-tech enough to be relatable to these folks who have had an onslaught of technology in their lives, especially in the past decade. Francis, my postmaster friend at the Saligao post office in Goa, forever lamented that the government did nothing to upgrade their server, pointing to his relic of a box computer.

It’s hard to find a letter box these days except outside a post office. Seeing the red box and the red van standing outside my neighbourhood P.O. in old MHB colony in Bombay where I lived most of my life (before I moved to Goa) somehow made everything feel better.

I realise that the post offices that left a mark on me are not the imposing white-domed, Corinthian-pillared structures like the GPOs in Bombay, Bangalore and Calcutta; rather the small, nondescript ones like Nihung in Kotagiri, Saligao in Goa and Jomsom in Nepal. Small, almost missable structures with large souls.

I have lost count of the occasions Francis accepted my parcel even when the server was down, assuring me that it would be sent and that I could pay later and collect my receipt. I’d missed this kind of warmth and camaraderie in Bombay post offices, which seemed to have a cold yet robust efficiency.

What I also love about the post office is that it is one of the last great equalising institutions. No fast-track access, no VIP lounges or business class, everyone gets in line and waits their turn, and God forbid, if it’s lunch time, you start all over at 2 p.m.

Sometimes the wait is long, sometimes the person at the other end is too exacting and will ask you to tape up all the open bits of that Amazon box you recycled, or type out your address on a white sheet of paper and paste it (interesting to note that there is almost never a stationery shop next to the post office, so that means going home and coming back again, which I have done, several times).

Sometimes, the person will punctiliously point out that you have written a wrong pin code.

Finally—and maybe this is what thrills me most of all—it is one place where things still have to be written down, slowly, painstakingly, not auto-generated like most things in our life. It is only when I deal with post offices do I realise how my handwriting has changed over the years, how I went from print to cursive to something in between, modern yet with a classic flourish that I reserve to dot my ‘i’s and cross my ‘t’s.

My relationship with the post continues even today. The crumbling yet efficient post office in my hill town at 7,000 feet above sea level has a bench where one can sit and stare at the clouds, a whiteboard timetable of trains arriving at and departing from the nearest big town and a notice stating—‘Pictorial Cancellation Available’.

I learn (from the Indian Philately Digest, as it happens) that a Pictorial Cancellation is a special postmark with a graphic design highlighting places and things of historical, religious or tourist interest. Apparently first issued in 1951, some heritage examples include ‘Sanchi, Bihar’ (November, 1952), ‘Qutub Minar’ (November, 1954) and ‘Ajanta’ (June, 1965).

I think of the ways in which time seems to slow down when I’m in the vicinity of a post office. It suits the life stage I am in. It makes me grin thinking that even those who have never stepped inside something as ‘downmarket’ and ‘out of it’ as a post office, have to, at some point, eat humble pie when the only way they can receive their Aadhaar card or driving licence is through India Post.

And maybe it even provides me with a feeling of security. I think, what if there’s a huge technological meltdown, and handwritten letters make a comeback? Just the thought makes me feel more human.

---

Lalita Iyer is an author and journalist. Her previous columns in the 'Reset' series can be read here and here

Also Read: L&T 3D printing a post office in Bengaluru

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines