Economy

Modi’s India more unequal than ever

The World Inequality Report 2026 points out that extreme inequality in India is neither natural nor unavoidable; it is the outcome of political and institutional choices

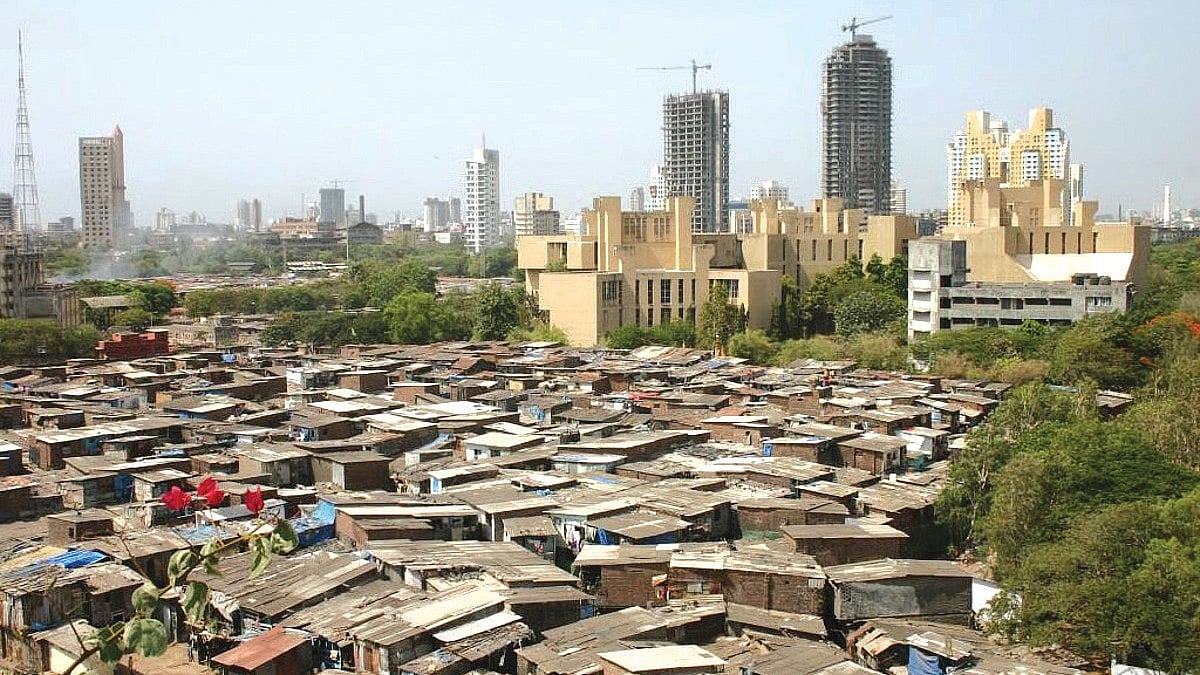

If there were an Olympic event for inequality, India would be a strong contender for gold. The World Inequality Report (WIR) 2026, published by the World Inequality Lab, confirms that India ranks among the countries with the highest concentration of income and wealth in the world. Its long-term analysis shows that India’s growth has disproportionately benefited a tiny elite, giving rise to what the authors describe as the era of the ‘Billionaire Raj’.

Economist Jean Dreze points out that the richest Indians are among the most pampered in the world today. They pay proportionately the lowest income tax, and pay neither wealth nor inheritance tax. The pandemic didn’t loosen their purse-strings, either.

The report offers striking evidence of India being one of the most unequal countries in the world. By 2022–23, the disparities between the ultra-rich and the rest had exceeded even the yawning disparities seen during the colonial period.

Income distribution figures are particularly stark: ‘The top 10 per cent of learners account for nearly 58 per cent of national income, while the bottom half of the population receives just about 15 per cent. Wealth inequality is even greater, with the richest 10 per cent holding around 65 per of total wealth and the top 1 per cent about 40 per cent.’

The report also highlights persistent gender disparities. At 15.7 per cent, female labour force participation remains far below the global average of 49 per cent and has shown almost no improvement between 2014 and 2024. Globally, women receive only about a quarter of total labour income, and this structural imbalance is far more severe in India.

According to the report, the extreme inequality we are seeing today is not accidental but the outcome of deliberate policy choices. In the decades following independence, up to the early 1980s, India had managed to keep income and wealth gaps within limits.

Published: undefined

This relative containment was rooted in the political and economic framework of the post-Independence period, which broadly followed a socialist orientation. Measures such as the nationalisation of key sectors and sharply progressive taxation played a central role. At its peak, the top marginal tax rate reached 97.5 per cent in 1973, significantly restricting wealth accumulation at the top and likely discouraging rent-seeking. During this phase, top income shares steadily declined, reaching their lowest point around 1982.

From the early 1980s onward, however, policy priorities began to change, culminating in wide-ranging economic liberalisation in the 1990s. This marked a decisive structural break. The surge in inequality since then is closely tied to the adoption of neo-liberal policies centred on market-led growth, deregulation, and reduced state intervention.

The period of economic liberalisation reversed the more egalitarian trajectory of the decades following Independence and sharply accelerated the concentration of wealth. Income and wealth at the top began to grow far faster than for the rest of the population. By 2022, the income share of the richest 10 per cent had almost doubled compared to its level in 1982. This process of extreme concentration meant that most of the gains from growth flowed to those who were already wealthy, producing what is often described as a ‘K-shaped recovery’.

The changing structure of India’s growth further deepened these inequalities. As the economy became increasingly reliant on the services sector and capital-intensive growth, returns to capital rose sharply, pushing up income shares at the top. At the same time, India failed to shift its vast workforce out of low-productivity agriculture into large-scale, high-wage manufacturing, unlike its regional counterpart, China.

This inability to generate broad-based, quality employment—combined with longstanding structural biases—has led to the gradual ‘hollowing out’ of the middle class. The middle 40 per cent of the population now accounts for only about 27–30 per cent of national income, far below the 40–45 per cent share seen in more equal economies. The result is a ‘dual economy’ in which a small, extremely affluent elite exists alongside a large and economically insecure majority.

Published: undefined

The WIR 2026 argues that inequality has been reinforced by chronic underinvestment in human capabilities. This rigidity is the outcome of sustained fiscal choices, particularly the stagnation of public spending on social sectors. Government expenditure on education has remained stuck at around 4 per cent of GDP for the past decade—well below the long-promised 6 per cent—while public healthcare spending has stayed limited at roughly 1.2–1.5 per cent of GDP. As a result, real per capita investment in human capital—the key driver of social mobility—has barely increased, leaving opportunities tightly rationed.

Evidence from local and micro-level studies support this assessment. While movement from agriculture to non-farm work has helped raise rural incomes and enabled some upward mobility within a generation, intergenerational mobility has weakened. Rural households are far less likely to have access to basic services such as piped water or clean cooking fuel even now. This infrastructure deficit imposes a heavy ‘time tax’ on the rural poor—especially women—and contributes directly to India’s exceptionally low female labour force participation.

The central conclusion of WIR 2026 is that extreme inequality in India is neither natural nor unavoidable; it is the outcome of political and institutional choices. Reversing this trajectory therefore requires conscious, sustained policy action. According to economist Jayati Ghosh, “These patterns are not accidents of markets. They reflect the legacy of history and the functioning of institutions, regulations and policies—all of which are related to unequal power relations that have yet to be rebalanced.”

Changes in taxation policy illustrate this dynamic clearly. In 2019, corporate tax rates were cut to stimulate growth and encourage job creation. Since then, however, the tax burden has shifted markedly. By 2023–24, personal income tax collections surpassed corporate tax revenues for the first time. During the same period, corporate profits nearly tripled—from Rs 2.5 trillion in 2020–21 to Rs 7.1 trillion in 2024–25, pushing the profit-to-GDP ratio to a 15-year high. Yet corporate loan write-offs remained substantial, amounting to Rs 6.15 lakh crore over the past five years, underscoring how policy choices have continued to favour capital over labour.

Published: undefined

The report’s most urgent recommendation is the introduction of strongly progressive taxation aimed squarely at the super-rich, in order to reverse India’s increasingly regressive tax structure. It points out that effective income tax rates often decline sharply at the very top, with billionaires paying a smaller share of their income than lower- and middle-income households by exploiting loopholes and holding wealth in lightly taxed assets.

India currently has no wealth tax, having abolished it in 2016–17, reflecting a broader global retreat from wealth taxation across OECD countries from the mid-1990s to 2018. The report proposes reintroducing such measures in the form of an annual wealth tax and an inheritance tax focused on the richest households. Even a modest minimum levy of 2 per cent on the net wealth of a few hundred of the wealthiest families could raise revenues equivalent to about 0.5 per cent of national income. These funds are vital not only to improve tax equity but also to create fiscal space for essential public investment.

However, redistribution through taxation must go hand in hand with a major expansion of public spending on core services. To break entrenched cycles of disadvantage, the state needs to substantially increase investment in education, healthcare, and public infrastructure. The report recommends adopting the ‘4As’ framework—available, affordable, approachable and appropriate public services—so they effectively reach the most marginalised sections of society, including rural populations and socially disadvantaged groups.

Tackling gender inequality, the report argues, requires addressing deep-rooted structural barriers. This includes enforcing equal pay and recognising unpaid care work through supportive policies such as affordable childcare, adequate parental leave, and pension credits for caregivers. Such measures are essential to ensure that economic opportunities are shaped by contribution rather than gender.

Finally, the report stresses the need to improve the quality, accessibility and transparency of government economic and tax data. Regular, reliable and publicly available data is crucial for independent research, public scrutiny and informed debate—key prerequisites for designing effective policies to reduce inequality.

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined