Nation

Tamil Nadu is celebrating a different centenary

Periyar’s Self-Respect Movement, which set the state on the path of social justice, turned 100 this year. K.A. Shaji reflects on its achievements

On a warm afternoon in a semi-rural primary school in Viralimalai, a village surrounded by rocky hillocks in Tamil Nadu’s Pudukkottai district, nine-year-old Mahalakshmi sits under a tamarind tree, her steel plate warm against her knees. The kitchen staff ladles out steaming rice, sambar and a mild vegetable curry as the children chatter softly. When the headmistress signals the start of the meal, the courtyard fills with laughter and clinks of metal. What looks ordinary is, in fact, living proof of one of Tamil Nadu’s greatest social revolutions.

The state’s Nutrition Meal Scheme — not to be confused with the Centrally sponsored Midday Meal Scheme (now renamed PM Poshan) — began in the mid-20th century as a modest government experiment, and has since grown into a comprehensive programme of fortified meals, eggs, fresh vegetables and, more recently, breakfast support from the M.K. Stalin government.

Educators say this is the most tangible expression of the Self-Respect Movement’s central demand that dignity must be material and equality a lived reality every day.

The headmistress, a veteran teacher, says the meal is the truest leveller she has seen in her career. Children from landless Dalit households, small OBC farms and migrant families eat together; there’s no hierarchy, no unease in the air. She says the programme defeats hunger and quietly rejects caste barriers. For her, this is the most authentic segue from Periyar’s radical dream.

How the ‘Self-Respect Movement’ rewired Tamil society

The centenary of the Self-Respect Movement invites a return to its origins. In the early decades of the 20th century, Tamil society was marked by suffocating caste hierarchies, Brahminical dominance in education and administration, and religious rituals that told millions they were inferior by birth.

Published: undefined

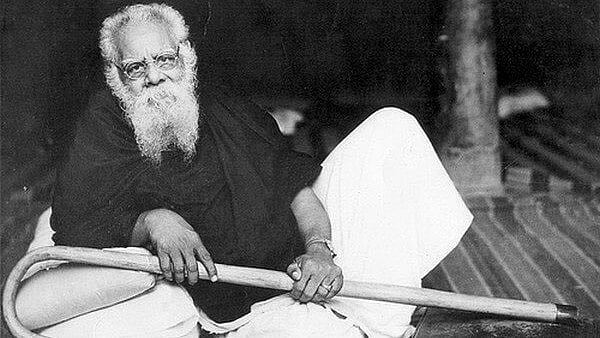

In 1925, E.V. Ramasamy, later known as Periyar, broke away from the Congress and the Justice Party to start a movement that demanded the annihilation of caste, the emancipation of women and the birth of a fearless, rational mind.

For Periyar, political freedom from the British mattered little if social enslavement persisted. He wrote that wisdom lay in thinking and that rationalism was the spearhead of thought. He urged ordinary people to question everything, including his own words. He encouraged inter-caste marriages, denounced the priesthood, attacked rituals that humiliated women, and insisted that Tamil identity carried dignity independent of northern cultural hegemony.

This rebellion created the ideological soil in which Dravidian politics later grew. The movement radically shifted the axis of Tamil politics from nationalism alone to internal liberation.

A welfare state rooted in equality

As Dravidian parties rose to power, they drew inspiration from the movement’s ethos. Tamil Nadu expanded reservations, strengthened the Public Distribution System, pioneered universal school meals, and invested heavily in public healthcare and education.

Over time, these measures reshaped the state’s development trajectory. Child malnutrition declined; infant mortality fell; literacy rose sharply; dropout rates plummeted. Scholars link these successes to a political imagination that grounded welfare in rational, anti-caste ethics rather than charity.

Sociologist M. Thiruvenkatam says Tamil Nadu’s welfare model is unique because it draws directly from the Self-Respect Movement’s ideological roots. He says the Nutrition Meal Scheme is not populism but a promise that emerged from a century of struggle.

The kitchens of the Nutrition Meal Scheme — which includes fortified foods, vegetables, eggs and grains — are today much improved, ensuring regular nourishment for millions of children.

Published: undefined

International observers frequently cite it as a successful model of linking school attendance with nutrition, and as an exemplar of social equality.

For students like Mahalakshmi, the impact is tangible and intimate. She says the meal keeps her awake in class and fuels her ambition to become a nurse. Her teacher too believes in the quiet ambition of this child who might otherwise have been lost to poverty and discrimination. Periyar must be smiling!

****

But the centenary celebrations must also acknowledge what Periyar would have called the movement’s unfinished business. Tamil Nadu continues to witness caste-based violence, particularly against Dalits. Attacks over inter-caste friendships, street access, temple festivities and burial grounds are still all too common in the state. Residential segregation survives in many villages. Land ownership remains uneven. Everyday rural life mocks the movement’s promise of equality.

Prof. C. Lakshmanan, a former faculty member of the Madras Institute of Development Studies, calls this the defining paradox of modern Tamil Nadu. He says the movement shattered Brahminical dominance at the top but was unable to fully democratise village-level power, where caste still dictates social relations. He argues that Tamil Nadu is progressive on paper and in policy, yet large swathes of its social terrain are still victims of caste conceit.

Dravidian renewal as bulwark

The centenary has arrived in a shifting political landscape. For decades, the state resisted Hindutva politics, but the BJP has gained visibility through outreach to certain caste clusters, temple-centred mobilisation, and appeals to young voters seeking cultural pride. Though still far from dominant, the party has succeeded in unsettling Tamil Nadu’s political vocabulary.

Published: undefined

DMK national spokesperson Salem Dharaneedharan says this is an ideological battle as much as an electoral one. He says Periyar fought to liberate society from fear and superstition, and that the BJP promotes a cultural project that quietly reinstates those forces. He believes defending Periyar’s legacy requires protecting the Nutrition Meal Scheme, the PDS, reservations and secular education.

The AIADMK’s shifty alliance with the BJP has deepened ideological confusion among its old guard, who still feel rooted in anti-caste Dravidian identity. Whether this disruption will reshape the state’s political future remains uncertain.

****

The Self-Respect Movement did succeed in breaking hierarchies, creating a political grammar of equality, and laying the foundations of a welfare state. But challenges remain: ending manual scavenging, improving the quality of schools and healthcare, protecting women from intersecting forms of violence, and confronting caste prejudice in daily life are urgent priorities.

Mahalakshmi washes her plate and prepares for afternoon class. The historical arc that brings her to this moment stretches from Periyar’s fiery speeches to the state’s carefully designed nutrition programme. She can dream of healing people because a welfare state protected her from hunger. Her teacher calls this the quiet revolution of Tamil Nadu.

A century ago, the Self-Respect Movement declared that no human being is born to bow their head. A century later, a child’s life chances expand because the state chooses to honour that promise.

In its centenary year, Tamil Nadu can do better than making the Self-Respect Movement a rallying cry against the forces of division; it can take the promise of the movement to the state’s farthest recesses, so that every child can dream like Mahalakshmi.

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined