POLITICS

Chennai: When the silver screen becomes a battleground

Release dates and festival slots are instruments of political signalling in Tamil Nadu

During Pongal in Tamil Nadu, everyday politics no longer announces itself from a party office, a secretariat corridor or a rally ground dusted with flags. It begins in the darkness of a cinema hall. Outside theatres, firecrackers burst before dawn, milk is poured on towering cut-outs, slogans echo with ritual familiarity, and the crowd that assembles already knows what it wants to believe.

What unfolds on the screen before them is not merely a film. It is a dress rehearsal, a collective act of remembering and anticipating, a reminder that in Tamil Nadu, cinema has long been the first ballot.

That is how Tamil Nadu has always done politics.

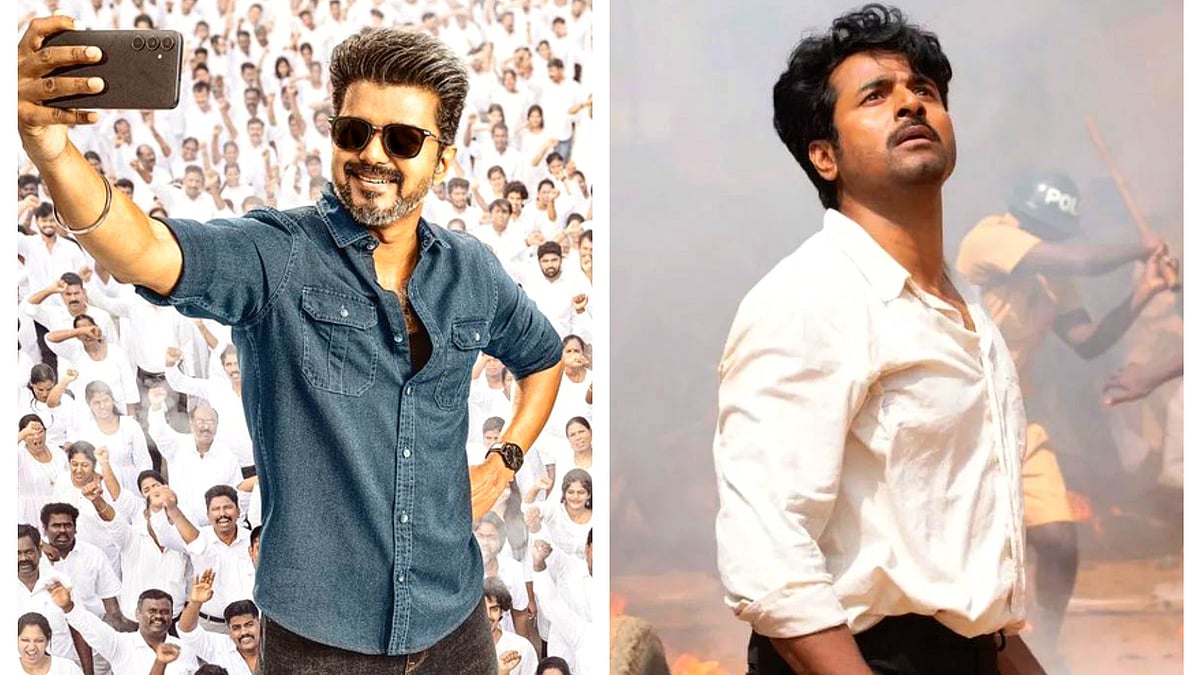

This Pongal, the argument was about what two films carried into the public imagination and what they sought to awaken. Parasakthi released in theatres after weeks of controversy, censor cuts and political sparring. Jana Nayagan, widely understood as actor Vijay’s farewell to cinema before he plunges fully into politics, was scheduled for release a day earlier, then abruptly postponed.

Between one film that arrived carrying the weight of history and another that did not arrive but refused to disappear from conversation, the Pongal box office became a political metaphor, with the upcoming Assembly election hovering as an unspoken subtext.

Tamil cinema has rarely been apolitical, but there are moments when it decisively alters the course of public life. The release of the original Parasakthi in 1952 was one such rupture.

Written by a young M. Karunanidhi at a time when mythologicals dominated the screen, the film shattered pieties and replaced them with a searing social critique. Religion was interrogated, caste hierarchy exposed, gender injustice confronted and Brahminical authority dragged into public debate. Audiences who entered theatres expecting reverence walked out unsettled, even angered, forced to question inherited beliefs.

Published: undefined

“Parasakthi taught people to listen differently,” said Salem Dharanidharan, national spokesperson of DMK, recalling how cinema became the Dravidian movement’s classroom. In 1967, when the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam captured power, the ideological groundwork had already been laid not in pamphlets or speeches but in cinema halls across the state, where voters had been emotionally prepared long before they were politically mobilised.

Seventy years later, the new Parasakthi draws directly from the anti-Hindi agitations of the 1960s, especially 1965, when Tamil Nadu erupted against what was perceived as cultural and linguistic domination by the Centre. That agitation, more than any manifesto, cemented the emotional foundations of Dravidian federalism. Language became resistance.

This history is not archival. It lives in family stories, in school lessons, in political memory that resurfaces whenever linguistic uniformity is pushed from Delhi.

****

The release dates sparked speculation of a proxy on-screen political battle between actor-politician Vijay and the ruling DMK: Jana Nayagan on 9 January and Parasakthi on 10 January. Even before audiences saw a single frame, the clash was framed as symbolic. Social media amplified it. Political camps interpreted it.

Then, Jana Nayagan was postponed. The delay only sharpened the political reading. In Tamil Nadu, timing is never accidental. Release dates, festival slots and first shows have long been instruments of political signalling.

Parasakthi is distributed by Red Giant Movies, now owned by Inban Udhayanidhi who succeeded his father, deputy chief minister Udhayanidhi Stalin. Inban is also the grandson of chief minister M.K. Stalin and the great-grandson of Karunanidhi, the original Parasakthi’s scriptwriter and the Dravidian movement’s most effective communicator. This lineage matters deeply in Tamil politics.

The 1952 Parasakthi was Sivaji Ganesan’s debut and Karunanidhi’s ideological breakthrough, establishing cinema as the Dravidian movement’s most potent instrument of mass persuasion.

Published: undefined

The new Parasakthi consciously draws from that tradition, blending historical fact with fictionalised narrative to tell the story of students from the erstwhile Madras Presidency who rose against Hindi imposition. It speaks to a generation for whom language politics may seem distant until it suddenly returns to the centre of national debate.

The film’s journey to release, marked by cuts and scrutiny, turned cinema into a site of institutional conflict. The DMK and its allies accused the Centre of weaponising the Central Board of Film Certification. The BJP rejected this charge. “If the Centre wanted to obstruct films politically, Parasakthi would have been the first to be stopped,” said BJP state leader S. Khushboo. “Red Giant is close to the DMK. But the CBFC only follows rules.”

On Jana Nayagan, Khushboo insisted the delay was procedural rather than political. “You cannot announce a release date without a CBFC certificate. That is the producer’s responsibility,” she said. “As a Vijay fan, I am upset too, but the rules apply to all.”

Congress MP Sasikanth Senthil offered a far darker reading. “They will not hesitate to use any institution. This is the power of fascism,” he said, arguing that Central institutions had become tools of control rather than neutral arbiters.

At the same time, he warned Tamil Nadu against losing sight of governance debates, pointing to changes proposed to employment schemes and welfare frameworks under the AIADMK-BJP alignment. The exchange revealed how cinema had once again become a proxy for deeper anxieties about federalism, autonomy and institutional trust.

Jana Nayagan’s politics is ethical rather than structural. Corruption is the enemy. Leadership is personalised. Justice flows from the hero’s moral authority rather than from collective struggle or institutional reform. This aligns precisely with Vijay’s political positioning so far.

Widely seen as his farewell to cinema before entering politics full-time, Jana Nayagan recalls an older Tamil tradition. M.G. Ramachandran, too, stepped away from the screen at the height of his popularity to convert cinematic charisma into political legitimacy.

Published: undefined

But there is a crucial difference. MGR inherited and reshaped Dravidian ideology. He entered politics through it. Vijay has so far kept his distance from that legacy. His Tamilaga Vettri Kazhagam does not claim the Dravidian inheritance; it seeks to position itself as an alternative to established binaries.

As Parasakthi began drawing audiences into debates on language, history and resistance, Jana Nayagan’s postponement created a different kind of momentum. For Vijay’s supporters, it reinforced the narrative of an outsider confronting entrenched systems. For the DMK, it allowed Parasakthi to occupy the cultural space unchallenged, at least temporarily, reaffirming its claim over the Dravidian cinematic tradition.

Early box-office patterns hinted at a familiar divide. Parasakthi found steady audiences in semi-urban and rural belts, among politically conscious viewers for whom language politics remains visceral and personal. Jana Nayagan, even before its delay, generated enormous buzz among urban youth and first-time voters, signalling where Vijay’s emerging strength lies. Neither constituency can be dismissed. Together, they map the fault lines of a changing electorate.

Tamil Nadu has seen this pattern before. Parasakthi prepared the emotional ground for DMK’s rise. MGR’s films turned benevolence into political charisma. Jayalalithaa’s screen authority translated into party dominance. This Pongal moment fits squarely into that lineage.

C. Laskhmanan, former faculty of Madras Institute of Development Studies, said, “Cinema does not decide elections in Tamil Nadu. But it often sets their emotional grammar. It tells voters what kind of contest they are entering before parties say a word. Karunanidhi once used cinema to teach people how to question power. Vijay is using it to ask whether they still trust those who inherited it. The answer will not be found in ticket sales or opening weekend numbers.”

It will emerge later, quietly, when the screen fades to black and the ballot boxes open.

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined